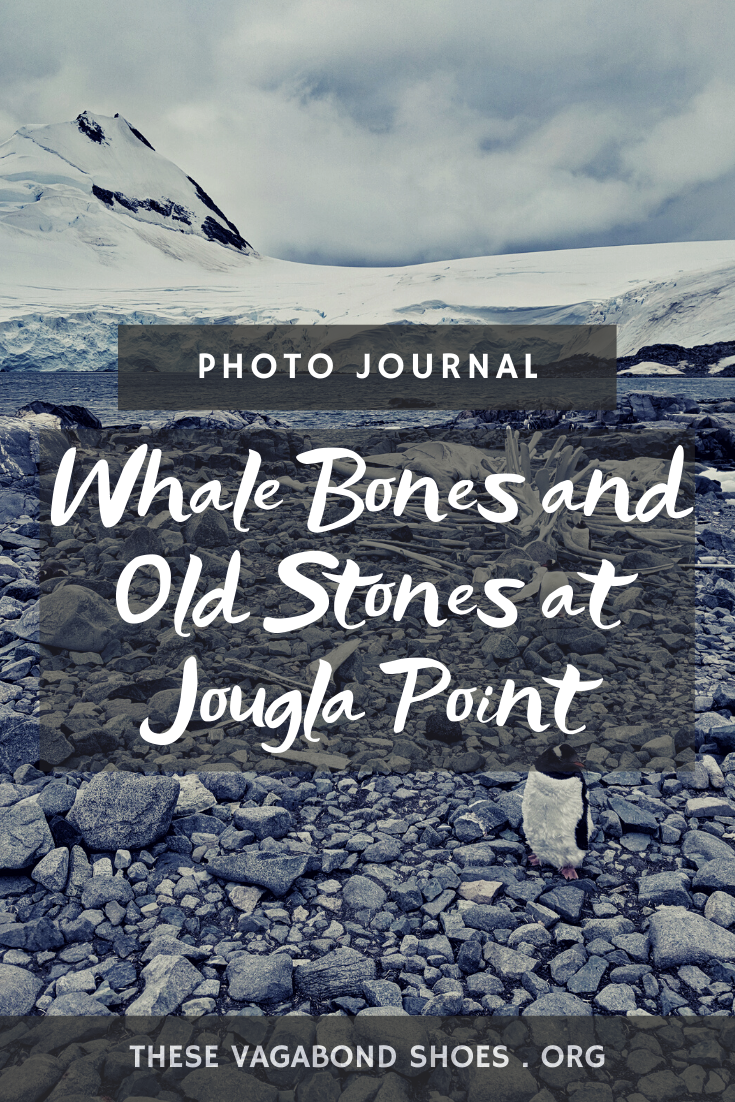

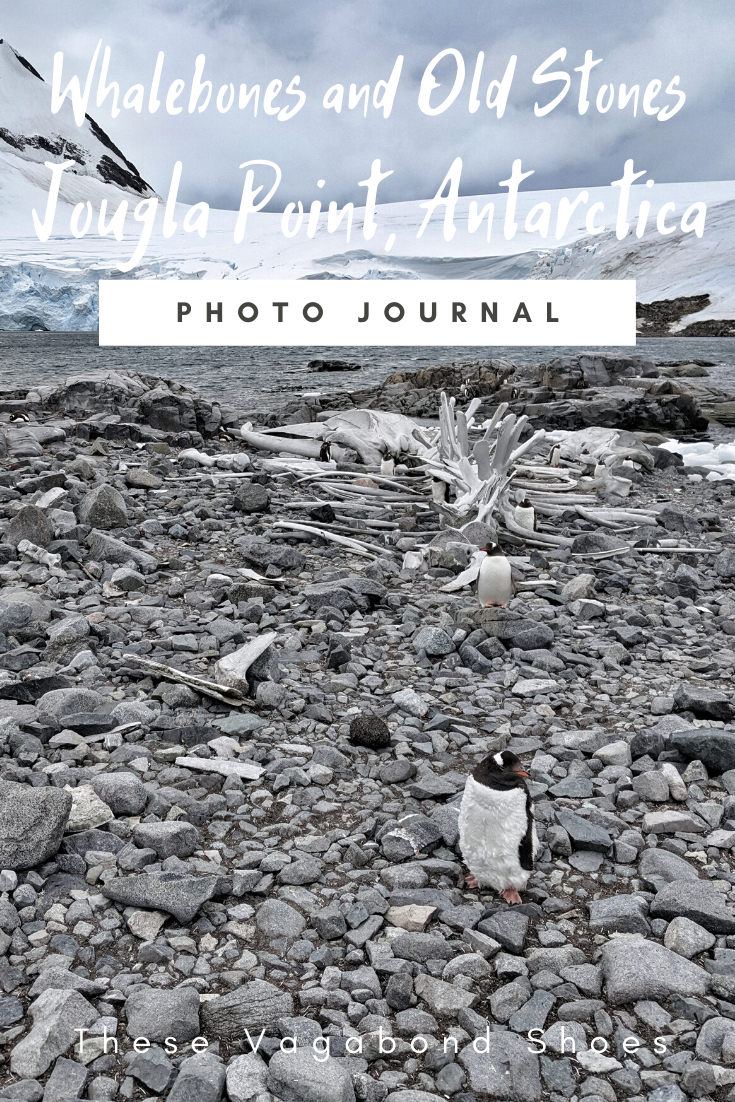

At first glance, Jougla Point is low rocky peninsula indented with small coves on the southern edge of the natural harbour at Port Lockroy, on the edge of Weinke Island. A colony of gentoo penguins occupy the peninsula during the breeding season, sharing space with blue-eyed shags and their prehistoric looking offspring, and on the ridge behind, rising steeply to the blue ice of Harbour Glacier, nest Antarctic skuas and kelp gulls.

Most visitors spend some time at Jougla Point in conjunction with their visit to Goudier Island, site of historic Base A, the first permanent British base on the Antarctic Peninsula, and home to the world-famous Penguin Post Office at Port Lockroy. And just like it’s near neighbour, a visit to Jougla Point reveals an insight into the history of human activity in Antarctica, though a glimpse of a darker, more industrial past.

As the tourist season progresses, snowmelt reveals a jumbled collection of weathered old whale bones among the granite stones. Rusted chains and shackles that once moored a large ship. A vast skeleton, a composite mainly constructed from the bones of fin whales is laid out in a cove. Further from the water’s edge, the rocks are covered with the scattered staves of old wooden barrels, and crumbling concrete footings show where buildings once stood.

Read: A Season at the Penguin Post Office in Port Lockroy

The Antarctic Whaling Industry

From the early 1900s, the majority of ships operating in Antarctic waters were part of the whaling fleet, or scientific survey vessels associated with the industry. Most had sailed from western Norway and eastern Scotland, signing crews from Dundee, Bergen, Leith, Sandefjord, Tórshavn, Larvik, and Lerwick.

The unknown qualities of Antarctica and the notoriously challenging conditions of the Southern Ocean were considered worth exploring, as traditional whaling grounds in the northern hemisphere had been exhausted. Bases were established on South Georgia and in the Falkland Islands to take advantage of the untapped resources of the South, though the human costs were high.

Floating factory ships soon ousted the need to transport whales to shore for processing, working alongside a small fleet of fast, agile whale catcher boats, which would chase down whales and harpoon them for factory ships to collect. The harpoons were explosive, lodging in the whale’s body before detonating a few seconds later, guaranteeing a kill.

The whalers charted large sections of the Antarctic Peninsula and the coast of Queen Maud Land (Dronning Maud Land), making their contribution to the knowledge of the continent, and often provided a safety net for expedition vessels on voyages of exploration early in the Heroic Age of Antarctica. But the intensity of their activity left an indelible impact on the ecosystem they exploited.

The Antarctic summer of 1930-31 was unprecedented, with the greatest number of whaling vessels operating in the Southern Ocean concurrently; 232 whale catcher ships taking their catches to 32 pelagic factory ships, nine floating factories moored in harbours like Port Lockroy, and six shore-based whaling stations. These were serviced by a fleet of supply ships, regularly bringing in food and fuel for the crews, and taking away processed whale oil for the global market.

In that season alone, records show that 29,410 blue whales were killed in the Antarctic, setting an all-time record for the exploitation of the species. Just over 30 years later, in the 1964-65 season, only 20 blue whales were killed, all that the hunters had observed.

The End of the Whaling Industry in Antarctica

More than 1.5 million whales were slaughtered in Antarctic waters before the International Whaling Commission (IWC) moratorium on commercial whaling was enforced in 1986.

By this time the industry was already in terminal decline, the result of over-exploitation of the whale stocks and increased regulation by the IWC reducing profitability. Companies faced the paradox that further hunting at existing levels would hasten the end of their industry, but there was no reward for showing restraint, and many of the key players diverted their interests into shipping freight or pelagic fishing.

The end of the whaling industry did not come from a position of nature conservation or animal welfare, but rather the loss of economic profitability from the sector.

The Return of the Whales

The Southern Ocean Whale Sanctuary was established in 1994. Covering an area of 50 million km2, including waters below latitude 60° South governed by the Antarctic Treaty System, it protects waters that provide summer feeding for an estimated 85% of all the world’s whales. The aim of the sanctuary is to enable the recovery of whale populations, not just in terms of absolute numbers, but also in the balance of sexes, age structures, and genetic diversity.

In early 2020, the British Antarctic Survey reported on the results of several years of expedition studies in the waters around South Georgia, suggesting that the long, slow road to recovery was now starting to show results. The observers recorded 55 different blue whales over 36 sightings in 2020, up from just one confirmed sighting in 2018.

Visitors to Antarctica, South Georgia, and the Falkland Islands can contribute photographs and details of any whale sightings they have on their voyage to the citizen science project Happy Whale and help be part of the efforts to monitor the return of the whales to Antarctic waters.

Have you visited Port Lockroy and Jougla Point? Let me know your thoughts in the comments below.

Did this post capture your imagination? Why not pin it for later?

Such incredible landscapes – even those bones look beautiful ✨